|

|

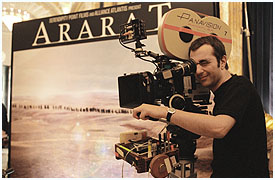

| Atom Egoyan über seinen Film: |

|

| ARARAT fragt nach der Rolle der Kunst im Ringen um Sinn und Erlösung nach einem Genozid. Es ist ein zutiefst persönliches Werk. Ich wollte keinen Film über den Genozid machen, sondern über die Erinnerung daran; und zeigen, wie Verleugnung das Trauma fortsetzt: Ständig muss man einen schmerzlichen Sachverhalt erklären, obwohl er der ganzen Welt bekannt sein sollte. Ich wollte die Folgen des historischen Ereignisses für unsere Generation aufspüren - und den Zuschauer das Grauen im spirituellen Sinn fühlen lassen: den Verlust der Menschlichkeit in uns. |

|

|

|

| Es gibt grossen Druck auf jeden armenischen Regisseur, "alles zu erzählen", den Film zu machen, der allen zeigen wird, was "wirklich geschah". Natürlich kann niemand sagen, was "wirklich geschah". Jede Erzählung, auch von Familiengeschichten, vermischt persönliche Geschichte, moralische Ansprüche, gesellschaftlichen Druck, geschichtliche Erfordernis. Die Herausforderung von ARARAT war, diesen Leitgedanken bei allen Figuren des Films zur Geltung zu bringen - zu zeigen, was sie tun, aber auch alle vorstellbaren Beweggründe für ihr Tun darzulegen. Es wäre unlauter, einen historischen Standpunkt vorzuführen, ohne die Möglichkeit eines anderen Standpunkts einzuschliessen. Auch wenn es praktischer wäre: die Wahrheit darf nie zum Monopol werden! |

»Geschichte muss man erzählen.

Das Leben leben.« |

|

| Atom Egoyan |

| Why This Film? |

|

| By Atom Egoyan |

|

| At the press conference for "The Sweet Hereafter" at Cannes in 1997, a journalist asked me if the film couldn't be seen as a metaphor for the Armenian Genocide. It was one of the few times in my life when I found myself quite speechless. The journalist went on to suggest that many of my films had dealt with themes of denial and its consequences, and was interested as to why I hadn't dealt with the subject more directly. |

|

| It was a good question. |

|

| I should begin with some personal facts. My grandparents from my father's side were victims of the horrors that befell the Armenian population of Turkey in the years around 1915. My grandfather, whose entire family save his sister was wiped out in the massacres, married my grandmother who was the sole survivor of her family. I never knew either of these people. They had both died long before I was born. |

|

| When my parents moved to Canada, they settled in Victoria--a city on the west coast where we were the only Armenian family. Though Armenian was my mother tongue, I was desperate to assimilate. Although I sometimes heard stories of what the Turks had done to my grandparents, I certainly wasn't raised with anger or hatred. I was too concerned with trying to be like all the other kids to dwell on these ancient grievances. |

|

| I left home at 18 to study classical guitar and international relations in Toronto. At the university, there was an active Armenian Students' Association, and I was exposed to an Armenian community for the first time. It's important to understand this was an extremely crucial moment in the evolution of Armenian politics. Armenian "terrorists" (or "freedom fighters," depending on your point of view) were beginning their systematic attacks against Turkish figures. Many Turkish ambassadors and consuls were being assassinated in this period, as Armenian extremists were enraged by the continued Turkish denial of what their grandparents had suffered. |

|

| I was completely torn by these events. While one side of me could understand the rage that informed these acts, I was also appalled by the cold-blooded nature of these killings. I was fascinated by what it would take for a person who was raised and educated with North American values of tolerance to get involved with these acts. One of the first feature scripts I ever wrote dealt with this issue. |

|

| Thankfully, I never made that film. At that point, 20 years ago, I wasn't ready to deal with the "Armenian Issue." |

|

| The problem with any film that deals with the "Armenian Issue," is that there are so many issues to deal with. First of all, there's the historical event. Since no widely-released dramatic movie had ever presented the Genocide, it was important that any film project would need to show what happened. We live in a popular culture that demands images before we allow ourselves to believe, and it would be unimaginable to deal with this history without presenting what the event looked like. |

|

| I believe that the most dramatic aspect of this history, however, is not the way it happened, but how it's been denied. Since the end of World War I, Turkey has refused to acknowledge the Genocide, going so far as to claim that it was in fact Armenians who committed genocide against the Turks. While this may seem preposterous, it is important to remember that there is now a generation of Turks who have been raised with this denial. They aren't denying anymore. It's what they've been led to believe. |

|

| From the moment I began to write this script, I was drawn to the idea of what it means to tell a story of horror. In this case, the horror isn't only about the historical events that took place in Turkey over 85 years ago, but also the enduring horror of living with something so cataclysmic that has been systematically denied. Without getting into the mechanics of that denial--there are a number of books and articles on that issue--it is important to note that the role of the director in my film-within-the-film is monumental. |

|

| Edward Saroyan, and his screenwriter Rouben, are faced with an awesome task. They will be the first filmmakers to present these images to a wide public. If their film seems raw and blunt in its depictions, it's because they are the first people to cinematically present these "unspeakable horrors." They are desperate to get the point across. |

|

| We learn that Edward's mother was a survivor of the Genocide--that he is making this film to honor her spirit. Needless to say, such noble personal intentions do not necessarily lend themselves to critical distance, and it's clear from the glimpses we see of Edward's movie that it might sometimes veer into an exaggerated and extreme view of history. Like many epics, it paints its heroes and its villains in an "over-the-top" way in order to heighten the sense of drama. Edward's "Ararat" is a sincere attempt to show what happened, told from the point of view of a boy who was raised with these images by his mother--a Genocide survivor. The scenes of the film-within-the-film represent the way many survivors and children who were told of these horrors would recall these events. |

|

| I decided to create this film-within-the-film in order to generate the drama in the present day. All of the central characters in my "Ararat" are somehow connected to the making of Edward's "Ararat," and most of the conflicts that occur in the contemporary story are related to the unresolved nature of not only the Genocide, but also the difficulties and compromises faced by the representation of this atrocity. How does an artist speak the unspeakable? What does it mean to listen? What happens when it is denied? |

|

| These are hugely complicated issues, and I certainly have enormous expectations of my viewer. While my work may have been different if a more popular movie version of the Armenian Genocide had already existed, this was not the case. Thus the screenplay had to tell the story of what happened, why it happened, why it's denied, why it continues to happen, and what happens when you continue to deny. |

|

| "Ararat" is a story about the transmission of trauma. It is cross-cultural and inter-generational. The grammar of the screenplay uses every possible tense available, from the past, present, and future, to the subjective and the conditional. I firmly believe that this was the only way the story could be told. It is dense and complicated because the issues are so complex. |

|

| History is not only the responsibility of the person who speaks the truth. It needs someone to listen. When that person listens, how they listen and why they listen are all essential components of the communication of experience. While the structure of "Ararat" is densely layered with these issues, I needed to show how the collective human linkage of action and responsibility is both the wonder and tragedy of our condition. |

|

| I couldn't have made this film any other way. |

| Arsinée Khanjian über ARARAT: |

|

| For actor Arsinée Khanjian, an Armenian-Canadian, who has appeared in many other Egoyan films including: Calendar, which she also co-produced; Exotica, during which she was pregnant with their son, Arshile; The Sweet Hereafter; and, most recently, Felicia's Journey, this film evokes strong personal passion."The first day I walked on the historical set for Charles Aznavour's 'Ararat', I cried" says Khanjian, whose grandparents survived the atrocities but were orphaned by the genocide. "I didn't even feel the emotion overtaking me…suddenly my face was just wet. I was realizing this was the first time in my life I was being in touch with an environment and with a group of people in their costumes and in their habitat to which I had no prior exposure. Of course, I knew much about the genocide and my own history but to see a re-creation of that time and place was just overwhelming for me."Khanjian is quick to point out, however, that this re-creation of Armenia in 1915 is not the central key of the film."The film is more about the people involved in making the historical epic 'Ararat,'" explains Khanjian, "than the historical epic itself. Atom has not made an educational film…It's about a group of characters - two families - all who have a history of their own that is not quite told or at least not heard.""It's about them discovering and coming to terms with the truths and denials in their own lives" continues Khanjian, "just like the Armenians have been trying to do for almost one hundred years. What the characters ultimately learn is their issues can go nowhere if there is no communication, if there are no truths being told, if there are no denials being admitted. They all come to realize that they have to tell something and then trust the fact what they are saying will be heard. It is only at that level of engagement they can move on with their lives and with each other." |

|